The world’s gliding mammals are an extraordinary group of animals that have the ability to glide from tree to tree with seemingly effortless grace. There are more than 60 species of gliding mammals including the flying squirrels from Europe and North America, the scaly-tailed flying squirrels from central Africa and the gliding possums of Australia and New Guinea.

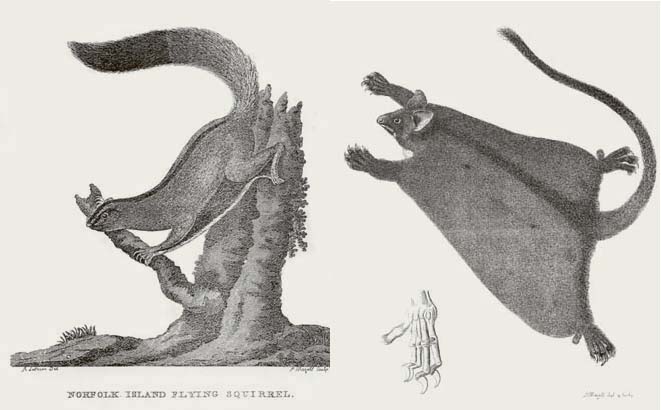

The Squirrel Glider was one of the first marsupial gliders to be discovered by Europeans. In 1789, a year after the First Fleet arrived in Australia, Governor Arthur Phillip noted that this species ‘inhabits Norfolk Island off the coast of New South Wales’ and called it the ‘Norfolk Island Flying Squirrel’. It was subsequently given the name Sciurus norfolcensis in recognition of its supposed squirrel origin, however it was later recognised as a marsupial and named Petaurus norfolcensis. Despite its name this species has never occurred on Norfolk Island and is only found down the east coast of Australia.

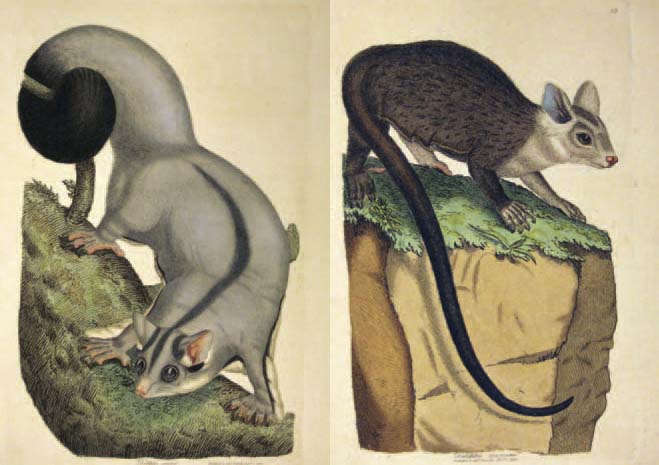

The Greater Glider was also recorded by Governor Arthur Phillip in 1789, who detailed several of its features:

The ears are large and erect; the coat or fur is of a much richer texture or more delicate than the sea otter ... on the upper parts of the body, at first sight, appearing of a glossy black, but on a nicer inspection, is really what the French call petit gris, or minever, being mixed with grey; the under parts are white, and on each hip may be observed a tan-coloured spot, nearly as big as a shilling; at this part the fur in thinnest, but at the root of the tail it is so rich and close that the hide cannot be felt through. The fur is also continued to the claws: the membrane, which is expanded on each side of the body, is situated much as in the grey species, though broader in proportion.

A few years later, in 1794, the English botanist and zoologist George Shaw described the Squirrel Glider in detail in his Zoology of New Holland:

In its general aspect this animal has so much the appearance of a squirrel, that on a cursory view it might readily pass for such. A more exact inspection into its characters will however evince it to be a genuine opossum ... The abdominal pouch is of considerable size, and is situated, as in other opossums, on the lower part of the abdomen. The hind feet are furnished with a rounded, unarmed, or mutic thumb. Nothing can exceed the softness and delicacy of this animal’s fur ... I must also add, that I have great reason for supposing the Petaurus to be furnished with an abdominal pouch; a particular which I have not yet been able to ascertain; no living specimens having been yet imported. The Opossum now described is a nocturnal animal, and continues torpid during the greatest part of the day, but during the night is full of activity.

Despite being a marsupial, the Yellow-bellied Glider was described by George Shaw in 1791 as a rodent flying squirrel. He noted that:

I thought it best to describe this animal as a species of flying squirrel, and to separate the flying squirrels from the genus Sciurus, with which Linnaeus had conjoined them, and to form them into a genus by the name of Petaurus. This perhaps may be thought an unnecessary piece of exactness; yet is something so peculiar in the expanded processes of skin by which the flying-squirrels are distinguished, that they may properly enough be allowed to form a distinct genus. Of all the species then of this genus the animal here figured is the largest and most elegant.

Several years later, in 1800, Shaw noted that ‘the size, colours, and form, of the Petaurine or great flying opossum of New Holland, conspire to render it one of the most beautiful of quadrupeds’. He described it as about ‘the size of a halfgrown cat or a small rabbet [sic]’.

The general appearance of the animal is similar to that of a flying squirrel; an expansile membrane, covered with fur, stretching from the fore legs to the hind on each side of the body, and thus enabling the animal to spring to a considerable distance at pleasure.

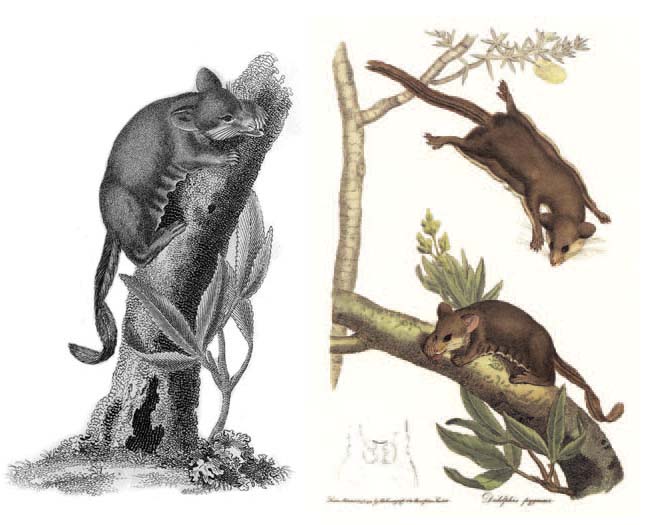

In his Zoology of New Holland, Shaw was the first to record the Feathertail Glider:

Amongst the most curious quadrupeds yet discovered in the Antarctic regions ... which (exclusive of its diminutive size, not exceeding that of a common domestic mouse) forms as it were a kind of missing link between the genera of Didelphis and Sciurus, or opossum and squirrel.

Subsequently, he noted that:

It is furnished on each side [of] the body with an expansile membrane, exactly in the manner of the flying squirrel; by the assistance of which it is enabled to spring to a considerable distance ... The tongue in this animal is remarkably large and long, and of flattened form: the hind feet have rounded and unarmed thumbs, and the two interior toes are united under a common skin. I am inclined to think that this species feeds on insects; and probably young birds, eggs ...

The great naturalist John Gould also made some detailed observations of the Feathertail Glider during his travels in Australia:

This pretty animal, the ‘Opossum Mouse’ of the colonists, is very common in every part of New South Wales; but from its nocturnal habits, its small size, and from the circumstances of its exclusively inhabiting the hollow limbs of the larger gum-trees, it rarely comes under the observation of ordinary travellers; it is in fact seen in considerable numbers only by those who really live in the bush, and to their notice it is seldom presented except under extraordinary circumstances, the most frequent of which are the blowing off of a large limb in which it is concealed: if this occurs in the daytime, the animal being in torpid state, does not make its appearance; but if, as occurred several times during my explorations, the limb be thrown upon the travellers fire, the little inhabitant is soon driven forth by the heat: occasionally as many as four or five are discovered by this means.

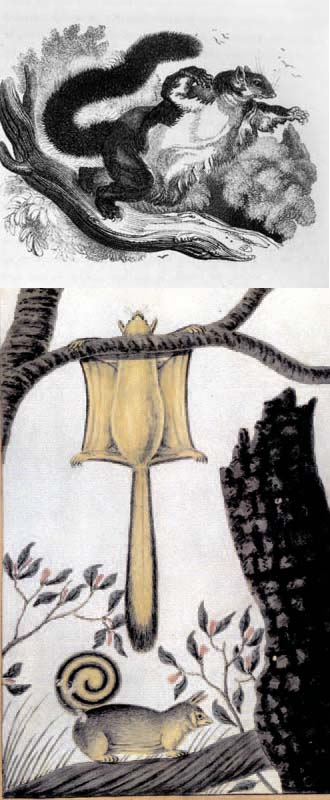

The first record of the Sugar Glider appears to have been made on 21 August 1803 in the Sydney Gazette:

A curious little native animal, partaking in appearance of the squirrel & native cat is at this time in possession of Dan McCoy ... The tail is of a remarkable length, the eyes rather prominent, the breast of a deep tan colour, and the back a dark mixture. On either shoulder, a thin skin expands itself, which probably assisted in its flight or spring from tree to tree. From its hoarse droning noise when handled or molested, it at present passes under the appellation of the buzzing squirrel.

The Sugar Glider quickly became a popular pet, and today some 50 000 individuals are reportedly held as pets throughout the United States of America. In 1909, the ornithologist Dudley Le Souef recorded:

A friend bought me one to Sydney from North Sydney. For some months he lived at large in my study. During the day he rested and slept on the top of the Venetian blinds of one of the windows, but as evening came on he would wake and fly down for his milk and biscuit or sugar. ‘Beauty’, as the children called him, would take his exercise by making flights from chair-back to chair-back, or from one of the children to another, alighting gently and without noise on the head or shoulder.

Sugar Gliders can be very inquisitive animals and were observed by the Norwegian zoologist and explorer Knut Dahl in his book In Savage Australia published in 1926:

Almost every morning these curious animals paid our camp a visit just before the break of day. They rummaged in our saddle gear and in our provisions and pack bags. But as soon as we moved to pick up a gun they would run swiftly up a large tree just in front of our awning, and spreading their parachute would sail into the dusk, disappearing before we could shoot.

The artist Thomas Skottowe made several drawings of the Squirrel Glider in 1813. He noted that:

This beautiful and innocent little animal lives in the large gum trees of the country on the berries of which it feeds. It has a membranous skin which extends from the fore to the hind feet, and which enables it with the help of its long bushy tail to fly or leap from tree to tree. The before mentioned skin acting as wings; it is very easily tamed. Native name, Billo.

A wonderful story of the Squirrel Glider’s gliding ability on a sailing ship was described in the Penny Cyclopedia in 1839:

On board a vessel sailing off the coast of New Holland was a Squirrel Petaurus, which was permitted to roam about the ship. On one occasion it reached the mast-head, and as the sailor who was despatched to bring it down approached, it made a spring from aloft to avoid him. At this moment the ship gave a heavy lurch, which, if the original direction of the little creature’s course had been continued, must have plunged it into the sea. All who witnessed the scene were in pain for its safety; but it suddenly appeared to check itself, and so to modify its career that it alighted safely on the deck.

While on his journey from Victoria to north Queensland the Norwegian explorer Carl Lumholtz, in 1889, made some observations on the Greater Glider and the hunting of them by the Aborigines:

Late in the evening my men heard the flying-squirrel (Petauroides) climbing the tall gum-trees above our heads, and the next day the blacks hunted these animals. Some of the men climbed the trees with the aid of their kãmins, in order to frighten them out from their abodes. Like chimney-sweeps they pulled the kãmins up and down in the hollow tree-trunks, at the same time shouting Po-pò! po-pò! in imitation of a night bird, and this po-pò was repeated by all those who stood below. The natives think that in this manner they can give the flying-squirrels the impression that it is night, and thus more easily coax them out. As a rule, they come forth quite suddenly, stretch their fliers, and fly slowly and elegantly into another tree, and while climbing the stem of this tree they are killed with sticks thrown at them.

They soon succeeded in frightening one of these animals out of a tree, and although the sun was shining in all its splendour, the squirrel landed with remarkable accuracy at the foot of a gum-tree eighty paces distant. While ascending the trunk I shot it.

Feathertail Glider

Acrobates pygmaeus

Flying Squirrel

Iomys sipora Mentawai

Indian Giant Flying Squirrel

Petaurista philippensis

Siberut Flying Squirrel

Petinomys lugens